SYSTEMS OF PHONETIC AND TONETIC

NOTATION AND SOME PROBLEMS

OF CONNECTED SPEECH

I. Phonetic Symbols

1.

Explanation of Narrow, Broad, and Extra-Broad Notation

Study of a language may be helped a great deal if sounds to be used in a given word or sentence are represented in some unambiguous say, so that there can never be any doubt which sound is meant. English, however, is a very badly spelled language. In it the same letter often stands for a number of distinctly different sounds as, for example, the letter a in hat, hate, hall, harm, etc. On the other hand, the same sound is represented by a variety of letters; for example, the vowel sound in bee is represented by ea in bean, eo in people, ie in piece, ei in receive, e in be, i in machine. An alphabetic system constructed on the basis of one symbol, and always the same symbol, foe each ‘distinctive’ sound, or and always the same symbol, for each ‘Distinctive’ sound, or ‘phoneme’1 is said to be phonetic. By making use of a phonetic alphabet a learner may avoid all those mispronunciations which one from relying on the traditional spelling. A word or sentence respelled in a phonetic alphabet will not only enable a learner to avoid the distracting influence of the traditional spelling, but also assist his auditory memory, since it appeals to the visual memory in a more unambiguous way than the traditional spelling.

When an alphabet with a clear one-for-one correspondence between a single graphic symbol and a single phoneme is used in a transcription, it is understood that one graphic symbol stands for one or other sound included in the phoneme, the choice being determined by simple principles which may be stated once for all. A transcription of this, type, i. e., ‘one symbol per phoneme’ type is called a Broad Notation.

A transcription may also make

use of different symbols to indicate two or more variant sounds included in

a phoneme instead of leaving the choice of a particular sound to be determined

by principles stated. For examples, the two l sounds in the word little,

which are regularly differentiated by many speakers of English, are transcribed

as [l] and ![]() , the principles for the choice of the two being that in the pronunciation

of such speakers the former variety is used before a vowel and the latter

before a consonant or finally. A transcription of this type, i. e., ‘more symbols than one per phoneme’ type is called

a Narrow Notation.

, the principles for the choice of the two being that in the pronunciation

of such speakers the former variety is used before a vowel and the latter

before a consonant or finally. A transcription of this type, i. e., ‘more symbols than one per phoneme’ type is called

a Narrow Notation.

There may be degrees of broadness or narrowness in either type of notation. Thus, a broad notation may make use of exactly the same number of different letters as that of the phonemes existing in a language; while the number of different letters may be minimized by making a letter do duty either with length-marks, with stress-marks, or by being combined with other letters, for two or more phonemes without violating the ‘one symbol per phoneme’ principle. A transcription that makes use of the minimum number of letters within the ‘one symbol per phoneme’ principle is called an Extra-Broad Notation, or Simplified (Broad) Notation.

The type of phonetic

notation used in

The importance of broad, and extra-broad or simplified (broad) transcription has come to be recognized in recent years as evidenced by preference given it over a narrow transcription for general purposes of teaching English as a foreign language. The merits of a narrow transcription have come to be doubted, except for showing fine distinctions, particularly dialectical, for, although an American or Britisher may use varieties of any phoneme, the designating of such delicate differences in transcription has not in general borne better results than teaching through the use of a phonemic transcription. In the Preface to a phonetic reader published recently Daniel Jones remarks, “Another commendable feature of the book is the use of ‘broad’, transcription, i. e. a system which employs the least possible number of special phonetic letters. It is the same as that used in Scott’s English Canversations.”2 It is significant, too, that the British Council uses an extra-broad or simplified transcription in its periodical entitled, English Language Teaching.

In one form of extra-broad or simplified transcription

the symbols ![]() in hair

(h

in hair

(h![]()

![]() ) and e in get

(

) and e in get

(![]() et) are levelled to e while the symbols

et) are levelled to e while the symbols ![]() in hum

and

in hum

and ![]() in about

are levelled to

in about

are levelled to ![]() . The levelling of the last two vowels is a recent tendency and

has provided grounds for controversy, pro and con, among teachers of English

as a foreign language. From a purely practical point of view the levelling of

. The levelling of the last two vowels is a recent tendency and

has provided grounds for controversy, pro and con, among teachers of English

as a foreign language. From a purely practical point of view the levelling of ![]() and

and ![]() , it seems, can be fully supported,

as well as that of

, it seems, can be fully supported,

as well as that of ![]() and i or

and i or ![]() and e, since substitution of one for the other

does not distinguish one word from another,

and also since English and American speakers often substitute one for the

other, both individually and dialectically.

and e, since substitution of one for the other

does not distinguish one word from another,

and also since English and American speakers often substitute one for the

other, both individually and dialectically.

Because of the importance of understanding fully the nature and purpose of phonemes the following quotation, almost in full, is taken from the Preface by Daniel Jones, to a phonetic reader.

“I believe this to be the first book ever published in which a correct pronunciation of English is recorded accurately by the simplest possible type of phonetic transcription, i. e. a system employing the minimum number of symbols which will keep all words distinct from each other. Such a system involves using only 29 letters, a length mark, a stress mark and (very occasionally) a syllabic mark. This is entirely adequate for teaching foreign learners how to use the English speech-sounds properly, after they have learnt how to make them.

“The idea of transcribing languages

by a phonetic system which is accurate and at the same time as simple as possible

is by no means new. The advisability of writing in this way was pointed out

by the great pioneer of practical phonetics, Henry Sweet, in his Handbook of Phonetics (1877), and the “Broad

Romic” used by him in his Elementarbuch des Gesprochenen Englisch

(first published in 1885) was actually a close approximation to the ideal

of simplest transcription. That system contained in fact only one superfluous

letter, namely ![]() ; if oo had been substituted for this, as

it might have been in conformity with the rest of Sweet’s system, Mr. Scott’s

style of transcription would have been anticipated 57 years ago.

; if oo had been substituted for this, as

it might have been in conformity with the rest of Sweet’s system, Mr. Scott’s

style of transcription would have been anticipated 57 years ago.

“Most subsequent writers on phonetics, myself among them, have departed to a greater or less extent from the ideal of simplest transcription. However, after working for many years with more elaborate forms of phonetic writing, I have now reached the conclusion that the supposed advantages of introducing more than the bare minimum of signs are illusory, and that the simplest type of transcription is the best for almost all purposes, and particularly in the teaching of a spoken language to foreign learners.”8

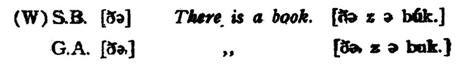

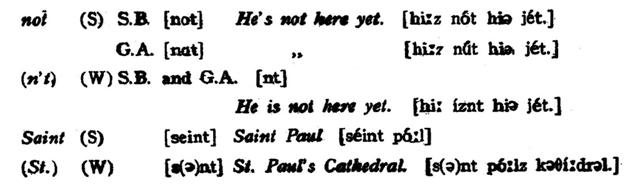

Readers are asked to study the following comparative table.

Comparative Table

Narrow Transcription:

![]()

Explanation:![]() accent; [l] clear l (in prevocalic

position);

accent; [l] clear l (in prevocalic

position); ![]() , dark l (before

consonant or final); [ph], aspirated

p;

, dark l (before

consonant or final); [ph], aspirated

p; ![]() ,half-length mark;

,half-length mark; ![]() quality of length mark: or

quality of length mark: or ![]() when

long; [

when

long; [ ![]() ], quality of relatively

more lax short

], quality of relatively

more lax short ![]() .

.

Broad Transcription:

![]() pit [pit],

bid [bid],

pit [pit],

bid [bid], ![]() hair

[h

hair

[h![]()

![]() ], high [h

], high [h![]() i], how [h

i], how [h![]() u],

u], ![]() American: [h

American: [h![]() f], and hum [h

f], and hum [h![]() m].

m].

Explanation: [l]

and ![]() are leveled to l, the distinction being

obtained by the phonetic context. [i] in

are leveled to l, the distinction being

obtained by the phonetic context. [i] in ![]() and [

and [ ![]() ]

are levelled to

]

are levelled to ![]() , the distinction being obtained by the

phonetic context. [

, the distinction being obtained by the

phonetic context. [![]() ] in [h

] in [h![]()

![]() ] has a different symbol than that

for the “closer” [e] in get. [a] in diphthongs such as high

and how, which is a front low vowel,

has a different symbol from the back low [

] has a different symbol than that

for the “closer” [e] in get. [a] in diphthongs such as high

and how, which is a front low vowel,

has a different symbol from the back low [![]() ] in

] in ![]() which is always long. [

which is always long. [ ![]() ] in hum has a different symbol from the obscure

vowel [

] in hum has a different symbol from the obscure

vowel [![]() ] which [

] which [![]() ] in Received Standard (British) occurs

only in unstressed positions.

] in Received Standard (British) occurs

only in unstressed positions.

Extra-Broad Transcription:

![]() pit [pit],

bid [bid],

pit [pit],

bid [bid], ![]() hair

[he

hair

[he![]() ], high [h

], high [h![]() i], or [hai], how [h

i], or [hai], how [h![]() u] or [hau],

u] or [hau], ![]() American [h

American [h![]() f], hum [h

f], hum [h![]() m].

m].

Explanation: Based strictly on the principle of one symbol for one phoneme.

2.

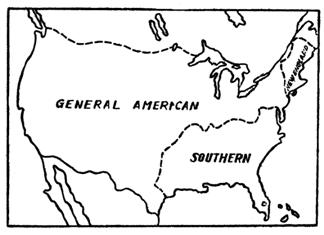

Comparison of So-called British and American Sounds

In connection with the problems of dialects or types of English, the following general observations may be found useful:-

(1) There are distinct variants of speech in every social class, and class variants in every district.

(2) Local variants become increasingly unlike one another in proportion to lack of education.

(3) They become more alike in proportion to increase in the amount of education acquired.

(4) The spread of education and the increased facility of oral communication tends to bring about the unification of the social variants in all districts.

(5) In

(6) In American those speakers who use a type of English having more features in common with Northern English than with Southern English seem to provoke least strangeness.

(7) The two

types of English regarded as the speech of educated people in

As a corollary of the above

considerations, it is desirable for Japanese students to learn the type of

speech used by educated people of either

Some of the chief differences between Southern British English and General American English are as follows:

|

Southern British |

General American |

|

(1) ‘r’ is sounded only before a vowel. |

‘r’ is sounded wherever it is spelt, and the l is pronounced as a retroflex [r] in colonel, all British |

|

(2) The vowel in half, last, path, dance is that in father. |

The vowel in half, last, path, dance is like that in bad. |

|

(3) The vowel in stop, hot is more like in quality to the short of the one in talk. |

The vowel in stop, hot sounds like the short of the one in father. |

|

(4) The vowels of take, made, and of note, rode are more diphthongal than in G. A. |

The vowels of take, made, and of note, rode are less diphthongal than in S. B. |

|

(5) The [j] sound is more usually retained in words like new, tune, due, suit. |

The [j] sound is more usually dropped in words like new, tune, due, suit. |

|

(6) The [h] sound is less often heard in words like what, which, when. |

The [h] sound is more often heard in words like what, which, when. |

|

(7) The [t] sound is seldom heard after the [n] in words like once hence. |

The [t] sound is often heard after the [n] in words like once, hence. |

|

(8) Words like dictionary, cemetery, dormitory have no secondary stress. |

Words like dictionary, cemetery, dormitory have a secondary stress. |

It may be worth while to

note that General American is a direct descendant of the standard English in

the seventeenth century, when

3.

Comparative Table of Types of Phonetic Symbols

The following tables contain only a few examples of those symbols that are based on the principle of using a district symbol, whether comprising a single letter or combination of letters, for each phoneme. This does not, however, imply that other systems of phonetic notation do not deserve our attention. Each system may have its special merit in respect of the purposes it is used to serve. For instance, Webster’s symbols that show the pronunciation by adding diacritical marks to the orthographic form may help to show the relation between the sounds and the spelling, though the system may result in encouraging the so-called spelling pronunciation at the expense of more natural and recommendable pronunciation of spoken English. Even the use of kona-gaki notation may be justified in thee very elementary stage as a feasible memory cure, if proper precautions are taken against distorting the pronunciation into a Japanaized one. It is a common sense to say that any letter can be used for any sounds, if only clear definition is given and a consistent use is made of it.

Generally speaking, however, the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet from an early stage of learning a foreign language has the approval of phoneticians and many progressive teachers. As early as in 1921 Dr. Harold E. Palmer said, “It has been ascertained experimentally that those who have been taught to read and to write a language phonetically become quite as efficient spellers as those not so trained. In many cases the phonetically trained student becomes the better speller.”4 Twenty-six years later, in 1947, P. A. D. MacCarthy says in an article in a professional journal, after discussing the use of phonetic transcription in the classroom in the initial stage, “At the next stage, the transition to ordinary spelling is made, systematically, going over again the language material that is already familiar. This serves as a valuable period of recapitulation. Experience has shown, moreover, that those who have been introduced to English spelling in this say, (i. e., after having worked with tile sounds only, for a preliminary period), so far from being confused by the change-over, actually make better spellers in the end (quite apart from making better speakers) than those who have been plunged into the intricacies of the current orthography from the start. This is doubtless due to the clear and orderly habits of thinking instilled by the systematic method of a well-managed transition.”5

If some teachers feel that phonetic spelling may interfere with the learning of orthographic spelling at some stage, such interference may be due to (1) teaching resulting from a lack of confidence and skill in the use of phonetic script and mishandling of the change-over, (2) lack of understanding or interest in the phonetic approach, (3) and consequent lack of understanding and interest on the part of the pupils, or (4) some cause quite divorced from the introduction of phonetic script. But even if there were interference with the learning of orthographic spelling, the pains of conquering the difficulty would be well compensated by the mastery of a good pronunciation. The difficulty, moreover, of learning new phonetic symbols will be minimized if an Extra-Broad transcription is used.

Table I Consonant Symbols

|

Key Words |

Type I |

Type II |

Type III |

Type IV |

Type V |

Type VI |

||||

|

pip |

[p] |

[p] |

[p] |

[p] |

[p] |

[p] |

||||

|

bob |

[b] |

[b] |

[b] |

[b] |

[b] |

[b] |

||||

|

tut |

[t] |

[t] |

[t] |

[t] |

[t] |

[t] |

||||

|

did |

[d] |

[d] |

[d] |

[d] |

[d] |

[d] |

||||

|

kick |

[k] |

[k] |

[k] |

[k] |

[k] |

[k] |

||||

|

gog |

[ |

[g] |

[ |

[g] |

[ |

[g] |

||||

|

fife |

[f] |

[f] |

[f] |

[f] |

[f] |

[f] |

||||

|

valve |

[v] |

[v] |

[v] |

[v] |

[v] |

[v] |

||||

|

thin |

[θ] |

[θ] |

[θ] |

[θ] |

[th] |

[θ] |

||||

|

than |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

say |

[s] |

[s] |

[s] |

[s] |

[s] |

[s] |

||||

|

zoo |

[z] |

[z] |

[z] |

[z] |

[z] |

[z] |

||||

|

show |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[sh] |

|

||||

|

azure |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[zh] |

[ |

||||

|

how |

[h] |

[h] |

[h] |

[h] |

[h] |

[h] |

||||

|

church |

[t |

[t |

[t |

[t |

[ch] |

[ |

||||

|

judge |

[d |

[d |

[d |

[d |

[j] |

[j] |

||||

|

mum |

[m] |

[m] |

[m] |

[m] |

[m] |

[m] |

||||

|

nun |

[n] |

[n] |

[n] |

[n] |

[n] |

[n] |

||||

|

king |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ng] |

[ |

||||

|

lull |

[l] |

[l] |

[l] |

[l] |

[l] |

[l] |

||||

|

way |

[w] |

[w] |

[w] |

[w] |

[w] |

[w] |

||||

|

whale6 |

[hw] |

[hw] |

[hw] |

[hw] |

[hw] |

[hw] |

||||

|

yet |

[j] |

[j] |

[j] |

[j] |

[y] |

[j] |

||||

|

rate |

[r] |

[r] |

[r] |

[r] |

[r] |

[r] |

||||

Table Ⅱ Vowel Symbols

|

bee |

|

[ii] |

|

[i] |

[ |

[ij] |

||||||||||

|

pity |

[i] |

[i] |

[i] |

[ |

[i] |

[i] |

||||||||||

|

bed |

[e] |

[e] |

[e] |

[ |

[e] |

[e] |

||||||||||

|

bad |

[ |

[a] |

[ |

[ |

[a] |

[ |

||||||||||

|

palm |

|

[aa] |

|

[ |

[ |

|

||||||||||

|

watch (S. B.) |

[o] |

[o] |

[ |

[ |

[o] |

[ |

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

[ |

|

[ |

[ |

[o] |

[ |

||||||||||

|

paw |

|

[oo] |

|

[ |

[ |

|

||||||||||

|

lord (S. B.) |

|

[oo] |

|

[ |

[ |

|

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

[o |

|

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

||||||||||

|

full |

[u] |

[u] |

[u] |

[ |

[u] |

[u] |

||||||||||

|

fool |

|

[uu] |

|

[u] |

[ |

[uw] |

||||||||||

|

bird (S. B.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

|

[-] |

|

[ |

[r] |

|||||||||||

|

mother(S. B.) |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

[ |

|

[-] |

[ |

[ |

[r] |

||||||||||

|

cut |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[u] |

[ [o] |

( also for G.A.) | |||||||||

|

pay |

[ei] |

[ei] |

[ei] |

[e] |

[ |

[ej] |

||||||||||

|

by |

[ |

[ai] |

[ai] |

[a |

[ |

[aj] |

||||||||||

|

boy |

[oi] |

[oi] |

[i] |

[ |

[oi] |

[ |

||||||||||

|

now |

[ |

[au] |

[au] |

[a |

[ou] |

[aw] |

||||||||||

|

go |

[ou] |

[ou] |

[ou] |

[o] |

[ |

[ow] |

||||||||||

|

ear (S. B.) |

[i |

[i |

[i |

[ |

[i |

[i |

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

[i |

|

[-] |

[ |

[ |

[ijr] |

||||||||||

|

air (S. B.) |

[e |

[e |

[ |

[ |

|

[ |

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

[e |

|

[-] |

[ |

[ar] |

[ejr]] |

||||||||||

|

four (S. B.) |

[o |

[o |

[ |

[ |

[ |

[ |

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

[o |

|

[-] |

[ |

[ |

[owr] |

||||||||||

|

poor (S. B.) |

[u |

[u |

[u |

[ |

[ |

[u |

||||||||||

|

-(G.A.) |

[u |

|

[-] |

[ |

[ |

[uwr] |

||||||||||

|

art (S. B.) |

|

[aa] |

|

|

[ |

|

||||||||||

| -(G.A.) |

[ |

|

[-] |

[ |

[ |

[ |

||||||||||

Notes on the Terms “Southern British” and

“General American”

The term “Southern British”

(abbreviated S. B.) is used to designate that form of English spoken most

commonly be educated people in

Most dictionaries published

in

recorded in his dictionary to be the type “most usually heard in everyday speech in the families of Southern English people who have been educated at the public schools,” the term ‘public school’ being used in the English sense. The pronunciation, however, is not confined to this class of people but is used also by those outside of this category.

The term “General American”

(abbreviated G. A.) is used to designate that form of English spoken most

commonly by people who live in about four-fifths of the area of the

Most dictionaries published recently in the

“In view of the vastly greater geographical extent of American English, it is understandable that there can be no single standard so conveniently formalized as we find for British usage. The closest approach to this, however, is what is commonly designated as General American pronunciation.”9

Remarks

The Symbols listed above are copied from the following sources:

Type I: R. H. Gerhard, A Handbook of English and American Sounds,

Type II: N. C. Scott,

Type III: D. Jones. An English Pronouncing Dictionary, Dent, 1937. Broad Transcription.

Type IV: J. S. Kenyon & T. A. Knott, A Pronouncing Dictionary of American English, Merriam, 1944. Narrow Transcription.

Type V: E. L. Thorndike, Thorndike Century Beginning Dictionary, Scott, Foresman, 1945.

Type VI: Leonard Bloomfield,

Language Henry Holt,

In preparing these tables we have had no intention to recommend any one particular type, though it may be regretted that so far no standard system of notation has been set up either at home or abroad. It is hoped that some unified form should come to be used by all dictionary compilers and textbook writers. In order to avoid needless complications, and in view of the various cries for simplified notation, we have used tentatively Type I symbols in the following pages.

II. Description of English

Sounds10

1. Vowels

Vowel sounds are characterized by the resonances formed in the mouth cavity, and these resonances depend primarily on the shape assumed by the mouth cavity in pronouncing a sound. In diagrams to show the vowel sounds, the “location” for each vowel represents the approximate position in the mouth cavity of the highest part of the tongue in the pronunciation of that sound. All English vowels are voiced, and care must be exercised against devoicing them ( as is often done in a Japanese word, such as shikashi) when they occur between breathed consonants.

(a)

Short Vowels: [i] [e] [![]() ] [

] [![]() ] [

] [![]() ] [

] [![]() ] [o] [u]

] [o] [u]

[i] is similar to short Japanese イ, but laxer and more central, so that it sounds somewhat intermediate between Japanese イ and エ.

[e] is similar to a short Japanese エ, but laxer and more open.

[![]() ] is between Japanese エand ア, with a “flat” or “shallow” quality produced

by a slight raising of the sides of the tongue. It is a help, too, to draw

back the corners of the mouth during the pronunciation of this sound.

] is between Japanese エand ア, with a “flat” or “shallow” quality produced

by a slight raising of the sides of the tongue. It is a help, too, to draw

back the corners of the mouth during the pronunciation of this sound.

[![]() ] is a little like Japanese ア, but the central

part of the tongue is higher and the sound is more obscure and deeper. When

unstressed, the sound is very short and obscure; when stressed, the tongue

is somewhat lower and more retracted, and the jaws are wider apart.

] is a little like Japanese ア, but the central

part of the tongue is higher and the sound is more obscure and deeper. When

unstressed, the sound is very short and obscure; when stressed, the tongue

is somewhat lower and more retracted, and the jaws are wider apart.

[![]() ] is entirely different from any Japanese vowel. One way of forming

this vowel is to raise the tip of the tongue and curl it more or less backward

toward the roof of the mouth, without actual contact of the point. Another

way of forming it is to raise the center of the tongue toward the roof of

he mouth. In both ways, there is considerable tensing of the muscles in the

pharynx. This sound does not occur in Southern British pronunciation, which

generally replaces it with [

] is entirely different from any Japanese vowel. One way of forming

this vowel is to raise the tip of the tongue and curl it more or less backward

toward the roof of the mouth, without actual contact of the point. Another

way of forming it is to raise the center of the tongue toward the roof of

he mouth. In both ways, there is considerable tensing of the muscles in the

pharynx. This sound does not occur in Southern British pronunciation, which

generally replaces it with [![]() ].

].

[![]() ] is much like Japanese ア, but with the

tongue more retracted and with considerable distension in the pharynx. The

jaws, too, are usually more open than for any other English vowel. Short [

] is much like Japanese ア, but with the

tongue more retracted and with considerable distension in the pharynx. The

jaws, too, are usually more open than for any other English vowel. Short [![]() ] does not normally occur in Southern

British pronunciation.

] does not normally occur in Southern

British pronunciation.

[o]

is somewhat similar to Japanese オ, but more open. This sound is not greatly different from a variety

of [![]() ] pronounced with rounded lips.

] pronounced with rounded lips.

[u] is very similar to Japanese ウ, but with the lips rounded and drawn in at the sides.

(b) Long Vowels: ![]()

![]() is similar to Japanese イー, but a little higher and more tensed.

is similar to Japanese イー, but a little higher and more tensed.

![]() resembles [

resembles [![]() ] but is longer and tenser, with the

central part of the tongue raised closer to the roof of the mouth and the

jaws very close together. This sound does not normally occur in General American

pronunciation.

] but is longer and tenser, with the

central part of the tongue raised closer to the roof of the mouth and the

jaws very close together. This sound does not normally occur in General American

pronunciation.

![]() is similar to [

is similar to [![]() ] but a little higher, longer, and more tensed. The jaws are very close

together. This sound does not occur in Southern British pronunciation.

] but a little higher, longer, and more tensed. The jaws are very close

together. This sound does not occur in Southern British pronunciation.

![]() is very similar to [

is very similar to [ ![]() ] but longer. The tongue is more retracted

than for Japanese アー, with greater distention in the pharynx.

] but longer. The tongue is more retracted

than for Japanese アー, with greater distention in the pharynx.

![]() is similar to Japanese オー, but a little more open. The back of the tongue

is higher than for short [o]-a little less so in American usage than in British-and

the lips are more closely rounded. There must be no movement of the tongue

or jaws during the pronunciation of this sound.

is similar to Japanese オー, but a little more open. The back of the tongue

is higher than for short [o]-a little less so in American usage than in British-and

the lips are more closely rounded. There must be no movement of the tongue

or jaws during the pronunciation of this sound.

![]() is similar to [u], but tenser and longer,

with the lips more closely rounded and drawn in at the sides.

is similar to [u], but tenser and longer,

with the lips more closely rounded and drawn in at the sides.

N. B. The longer

varieties of [![]() ], sometimes transcribed as

], sometimes transcribed as ![]() , and [e], sometimes transcribed as

, and [e], sometimes transcribed as

![]() , are not listed above as they are

used only as variant forms.

, are not listed above as they are

used only as variant forms.

(c)

Diphthongs: [ei] [![]() i] [oi]; [i

i] [oi]; [i![]() ] [e

] [e![]() ] [o

] [o![]() ] [u

] [u![]() ]; [

]; [![]() u] [ou]; [i

u] [ou]; [i![]() ] [e

] [e![]() ] [

] [![]()

![]() ] [o

] [o![]() ] [u

] [u![]() ]

]

The English diphthongs, though written with two vowel symbols, are really monosyllabic glides between two vowel positions, with greater prominence at the beginning of the glide. These digraphs, therefore, are to be interpreted as composite symbols, the first element being given full vowel quality in pronunciation, while the second element serves only to indicate the direction and approximate termination of tongue movement in the glide. With this general explanation, and with the accompanying diagrams to show relative tongue positions, the diphthongs should require little additional description.

[ei] and [ou] both start from considerably higher tongue positions than for those for short [e] and [o], respectively, and the starting position fro [ou] is normally more central and a little lower in British usage than in American.

For both [![]() i] and [

i] and [![]() u], also, the starting position of the

tongue is commonly more advanced than for short [

u], also, the starting position of the

tongue is commonly more advanced than for short [![]() ].

].

The diphthongs moving toward [![]() ] do not occur in General American

pronunciation, though the combination [i

] do not occur in General American

pronunciation, though the combination [i![]() ] occasionally occurs in that form

of speech as a dissyllabic juncture of two vowels, e.g., as in idea

] occasionally occurs in that form

of speech as a dissyllabic juncture of two vowels, e.g., as in idea

![]() .

.

The diphthongs moving

toward [![]() ] do not occur in Southern British pronunciation. When followed

by a vowel, a diphthong moving toward [

] do not occur in Southern British pronunciation. When followed

by a vowel, a diphthong moving toward [![]() ]− i.e. [i

]− i.e. [i![]() ], [e

], [e![]() ], [

], [![]()

![]() ], [o

], [o![]() ], or [u

], or [u![]() ]− and the corresponding combination

of a vowel and [r] −i.e.,[ir],[er],[

]− and the corresponding combination

of a vowel and [r] −i.e.,[ir],[er],[![]() r],[or], or [ur] −are pronounced in practically the same way in General American speech;

e.g., as in hairy [h

r],[or], or [ur] −are pronounced in practically the same way in General American speech;

e.g., as in hairy [h![]()

![]() i] and very [v

i] and very [v![]() ri]. The former transcritption, however, appears to be preferable when the

diphthong with [

ri]. The former transcritption, however, appears to be preferable when the

diphthong with [![]() ] is at the end of the root-word and the vowel that follows

is party of the suffix added to the root-word, e.g., poorer

[p

] is at the end of the root-word and the vowel that follows

is party of the suffix added to the root-word, e.g., poorer

[p![]()

![]()

![]() ], but rural [r

], but rural [r![]() r

r![]() l]; bearing [b

l]; bearing [b![]()

![]() i

i![]() ],

but burial [b

],

but burial [b![]() ri

ri![]() l].

l].

2.

Consonants

Consonant sounds are characterized by differences in place and manner of articulation. Again, some are “breathed” (i.e., pronounced with breath only), and some are “voiced” (i. e., pronounced with breath to which tone has been added by vibration of the vocal cords). In all cases, however, it is important to dissociate consonants from any accompanying vowel sound and also to learn to join consonants together according to the English speech habits.

(a)

Plosives: [p], [b]; [t], [d]; [k], [![]() ].

].

[p], [t], and [k] are breathed, while [b], [d], and [![]() ] are voiced. These sounds are practically the same as in Japanese

but care must be exercised to avoid adding any vowel sound when they occur

at the end of English words, and also to avoid making a plosive [

] are voiced. These sounds are practically the same as in Japanese

but care must be exercised to avoid adding any vowel sound when they occur

at the end of English words, and also to avoid making a plosive [![]() ] a nasal [

] a nasal [![]() ]when

[

]when

[![]() ] is really needed in a word.

] is really needed in a word.

The lips must be firmly closed

for [p] and [b], the tips of the tongue placed against the upper teethridge for [t] and [d], and the back of the tongue raised

to the soft palate for [k], and [![]() ]. For all

of these sounds the nasal passage is closed by the raising of the uvula.

]. For all

of these sounds the nasal passage is closed by the raising of the uvula.

(b) Nasals: [m], [n], [![]() ].

].

These are voiced sounds pronounced

through the nose. For [m] the lips are closed, for [n] the tip of the tongue

is placed against the upper teethridge, and for

[![]() ] the back of the tongue is raised to the soft palate. When a vowel

sound follows, [m] and [n] are similar to the Japanese consonants in ma-gy

] the back of the tongue is raised to the soft palate. When a vowel

sound follows, [m] and [n] are similar to the Japanese consonants in ma-gy![]() and na-gy

and na-gy![]() respectively, while [

respectively, while [![]() ]

is similar to the consonant sound in ga as pronounced

by many persons in the middle of a word-e. g., as in hagaki ha

]

is similar to the consonant sound in ga as pronounced

by many persons in the middle of a word-e. g., as in hagaki ha![]() aki.

In final position all three are slightly lengthened but otherwise unchanged,

and so are radically different from the Japanese [

aki.

In final position all three are slightly lengthened but otherwise unchanged,

and so are radically different from the Japanese [![]() ]

(=ン), as in hon [ho

]

(=ン), as in hon [ho![]() ].

The sound [

].

The sound [![]() ]

never occurs at the beginning of an English word.

]

never occurs at the beginning of an English word.

(c) Lateral: [l].

This is a voiced sound pronounced around the sides of the narrowed tongue, with the tongue-tip touching the upper teethridge. In articulating this sound the back of the tongue may be either raised toward the roof of the mouth or lowered down away from it. Acoustically the former articulation gives a “dark” sound, and the latter a “light” or “clear” sound somewhat similar to Japanese ウ. Most people use the “light” l before vowels and the “dark” l before consonants or in final position.

(d)

Fricatives: [f], [v]; [θ],![]() ; [s], [z]; [

; [s], [z]; [![]() ], [

], [![]() ]; [h].

]; [h].

[f], [θ], [s], [![]() ], and

[h] are breathed sounds, while [v],

], and

[h] are breathed sounds, while [v], ![]() , [z], and [

, [z], and [![]() ] are voiced. All fricative consonants are produced by expelling the

air-stream through a very narrow passage formed in the mouth or, in the case

of [h], the glottis. They are sometimes called “continuants” because the can

be prolonged as long as the breath lasts.

] are voiced. All fricative consonants are produced by expelling the

air-stream through a very narrow passage formed in the mouth or, in the case

of [h], the glottis. They are sometimes called “continuants” because the can

be prolonged as long as the breath lasts.

[f] and [v] are characterized by audible friction between the upper front teeth and the lower lip.

[θ] and ![]() are characterized by audible friction between

the tip of the tongue and the upper front teeth.

are characterized by audible friction between

the tip of the tongue and the upper front teeth.

[s] is the same as the breathed consonant sound in Japanese サ, ス, セ, ソ, with the breath directed along a narrow channel over the center of the tongue and the characteristic friction produced between the blade of the tongue and the upper teethridge. [z], which is voiced, is identical with [s] in every other way.

[![]() ] is similar to the breathed consonant sound in Japanese シ, but characteristically with stronger friction,

produced between the front of the tongue and the fore part of the hard palate.

] is similar to the breathed consonant sound in Japanese シ, but characteristically with stronger friction,

produced between the front of the tongue and the fore part of the hard palate.

[![]() ] is voiced, but is identical with [

] is voiced, but is identical with [![]() ] in every other way.

] in every other way.

[t![]() ] and [d

] and [d ![]() ], sometimes classified as affricate consonants, are formed in the

same way as [

], sometimes classified as affricate consonants, are formed in the

same way as [![]() ] and [

] and [![]() ] respectively, with a preceding plosive stop made by bringing the

tip of the tongue in contact with the teethridge

before the fricative consonants.

] respectively, with a preceding plosive stop made by bringing the

tip of the tongue in contact with the teethridge

before the fricative consonants.

[h] is a breathed glottal fricative, articulated by a partial closing of the vocal cords, in which neither the tongue nor the lips should have any part. It is, therefore, practically the same as the breathed consonantal part of Japanese ハ, ヘ, or ホ, but different from that of ヒ (where the friction occurs between the raised tongue and the roof of the mouth) or in フ(where the friction occurs between the two rounded lips). This sound never occurs at the end of an English word, though the letter h sometimes does in traditional spelling.

(e) Semivowels: [j]; [w]; [r].

An English semivowel is a voiced gliding sound in which the speech organs start from a vowel position and immediately change to that of whatever vowel it precedes. It is always short and nonsyllabic, and is used only in prevocalic position.

[j] is a semivowel starting from the position of a high, tensed [i]. When it precedes the vowel [i], it starts from a higher and more tensed position.

[w] is a semivowel starting from the position of a high, tensed [u]. When it precedes the vowel [u], it starts from a higher and more tensed position, with closely rounded lips.

[r] is a semivowel starting from the position of a high, tensed [![]() ]. When it precedes the vowel [

]. When it precedes the vowel [![]() ], it starts from a higher and more tensed position. In Southern British

pronunciation, [r] is also sometimes fricative in initial position, with the

blade of the tongue then raised closer to the teethridge.

], it starts from a higher and more tensed position. In Southern British

pronunciation, [r] is also sometimes fricative in initial position, with the

blade of the tongue then raised closer to the teethridge.

III. Stress Marks and Tonetic Symbols

1.

Methods of Marking Stress

“Stress is defined as the degree of force with which a sound or syllable is uttered.”11 In polysyllabic words it is usually possible to distinguish many degrees of stress. If we take the word ability, we can hear that the strongest stress fails on the second syllable, the weakest on the third, and the next weakest on the first, or, to show this in figures we could say that the word ability has [3-1-4-2] stressing, 1 standing for the strongest, 2 for the second strongest, etc. But for practical purposes such fine-cut accuracy is not needed. The main thing a student wants to know in learning a word is which syllable in it carries the chief stress. Words that have two stressed syllables are said to have ‘double stress.’ Occasionally we distinguish three degrees of stress: ‘primary stress,’ ‘secondary stress,’ and ‘no stress.’ For example, the word examination contains syllables of ‘no stress,’ ‘secondary stress,’ ‘no stress,’ ‘ primary stress,’ and ‘no stress.’

One way of indicating stress

in a phonetic transcription is to put a stress mark ![]() for primary stress and

for primary stress and ![]() for secondary stress; or

for secondary stress; or ![]() for primary stress and

for primary stress and ![]() for secondary stress. Thus, ability is marked

for secondary stress. Thus, ability is marked ![]() or

or ![]() and examination

is marked

and examination

is marked ![]() or

or ![]() The use of vertical marks before the stressed

syllables is the practice observed by most recent phoneticians in

The use of vertical marks before the stressed

syllables is the practice observed by most recent phoneticians in

In Japan there has been for many years another way of indicating stress,

namely, by putting the stress mark ![]() for primary stress and

for primary stress and ![]() for secondary stress right above the vowel symbol of the stressed

syllable.12 This may be justified by the fact that the center of

the stress is always on the vowel, and also by the fact that the stress may

actually begin midway in the articulation of a consonant, thus making it difficult

to show exactly where the syllable is to be divided13. It may be

added that in the case of diphthongs, also known as kinetic vowels, the mark

is placed over the first element, because in English there is an intra-syllabic

accent on the first component. For instance,

for secondary stress right above the vowel symbol of the stressed

syllable.12 This may be justified by the fact that the center of

the stress is always on the vowel, and also by the fact that the stress may

actually begin midway in the articulation of a consonant, thus making it difficult

to show exactly where the syllable is to be divided13. It may be

added that in the case of diphthongs, also known as kinetic vowels, the mark

is placed over the first element, because in English there is an intra-syllabic

accent on the first component. For instance, ![]()

![]()

There are other methods of

showing stress. Webster’s system has the stress mark ![]() for primary stress or

for primary stress or ![]() for secondary stress placed after the stressed

syllable instead of before it. It is unfortunate that there exist two entirely

opposite positions for stress marks. To underline or encircle a stressed vowel

or syllable may be mentioned as an optional way of marking stress in an unambiguous

way.

for secondary stress placed after the stressed

syllable instead of before it. It is unfortunate that there exist two entirely

opposite positions for stress marks. To underline or encircle a stressed vowel

or syllable may be mentioned as an optional way of marking stress in an unambiguous

way.

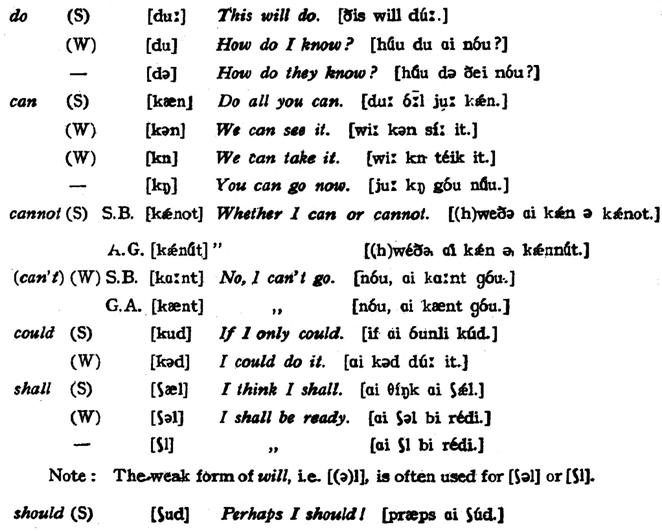

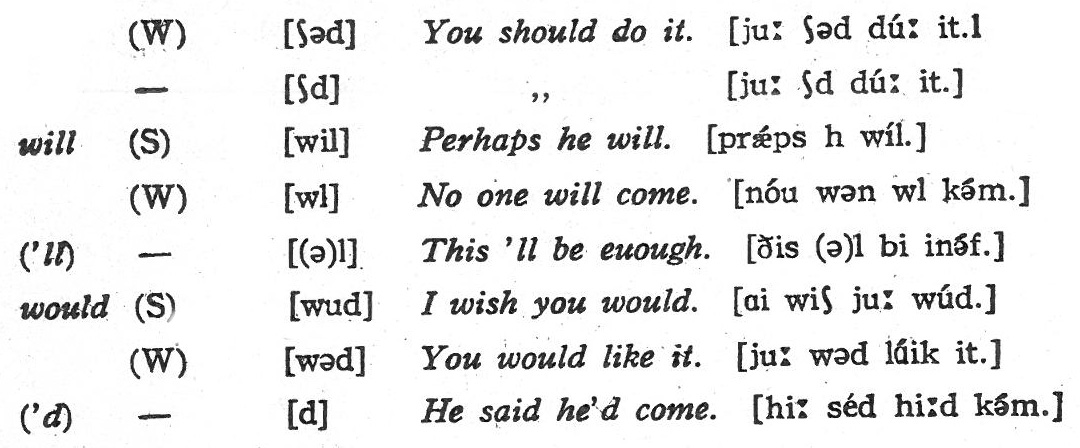

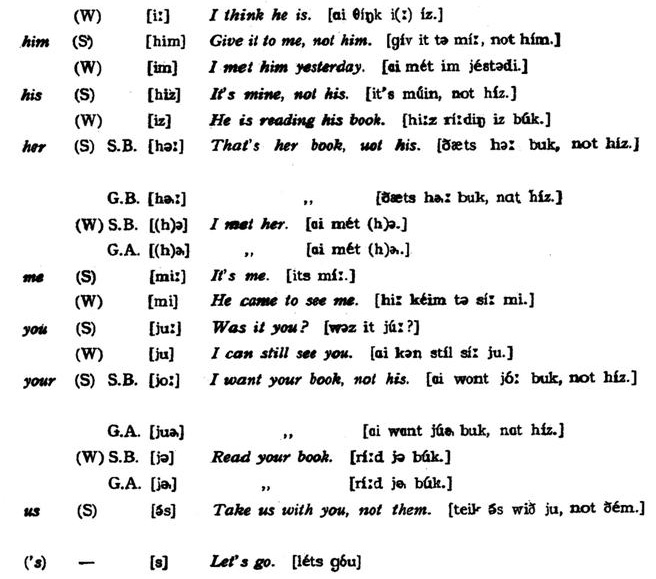

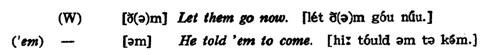

2. Word Stress and Sentence Stress

Every English word whether mono- or polysyllabic, has at least one stressed syllable when it is pronounced separately. In most dictionaries the stress mark is not given in the case of monosyllabic words, but this does not mean that such words have no stress. Stress we hear in words pronounced separately is called ‘word-stress.’

Stress in English words is a very important feature of the language. It cannot be learned by means of simple rules. In many cases there is no rule as to the position of stress, and when rules can be formulated, they are generally subject to numerous exceptions. It is therefore necessary for us to learn the stress of each word individually.

When words are in a group, they are not pronounced in the same way as when they are pronounced separately. Some words lose their stress altogether and others retain theirs more or less. In general, the relative stress of the words in groups depends on their relative importance in meaning. The more important words are, the stronger is their stress. Usually words that convey important meanings are what are called content words: namely

1. nouns,

2. principal verbs (verbs which do not stand in an auxiliary position before other verbs),

3. adjectives,

4. adverbs of time, place, and manner,

5. demonstratives,

6. interrogatives, and,

7. indefinite pronouns.

Words that do not usually carry important meanings are what are called function words; namely,

1. pronouns (personal and reflexive),

2. auxiliary verbs (used before other verbs),

3. prepositions,

4. connectives (conjunctions, relative pronouns, etc.),

5. articles, and

6. adverbs of degree.

Sentence stress is by no means fixed in all contexts. As the center of the speaker’s attention is shifted according to the context, function words may also have sentence stress.

Examples of Sentence Stress Marks

What do you think of the weather?

![]()

I think it will be quite warm tomorrow.

![]()

This express train often arrives late.

![]()

He told me that that that that that boy used was right.

![]()

3.

Nature of Intonation

Intonation is defined as “the variations which take place in the pitch of the voice in connected speech.”15

Every language has its characteristic tunes, its own typical types of tones, or in terms of modern phonetics intonation patterns or intonation contours.16 When one language is spoken with the intonation of another language, it is often difficult to understand it or at least gives the effect of strangeness or unnaturalness. In many languages, notably in English, intonation has an important role of adding various shades of meaning, showing the speaker’s attitude to the lexical or dictionary meaning of the words used.

In tone languages, of which Japanese is one, the intonation is fixed on words. Thus, in standard Japanese, the word hashi, bridge, is always pronounced with a lower tune on the first syllable in any kind of context, while hashi, chopsticks, is always pronounced with a high tune on the first syllable. On the contrary, in stress languages, of which English is one, intonation is never fixed on words when standing in context; it is changed freely in various ways according to context. Thus, the word pencil in a sentence like “I have a pencil” (and ordinary statement) is, as is the case with the word apart from its context, pronounced with a higher pitch (accompanying the stress) on the first syllable, while the same word in a sentence like “Have you a pencil?” (an ordinary question), is pronounced with a lower pitch (accompanying the stress) on the first syllable. Sometimes the variations of pitch (from high to low or vice versa) are great, sometimes slight, and sometimes more complicated than a mere rise or fall.

4.

Methods of Marking Intonation

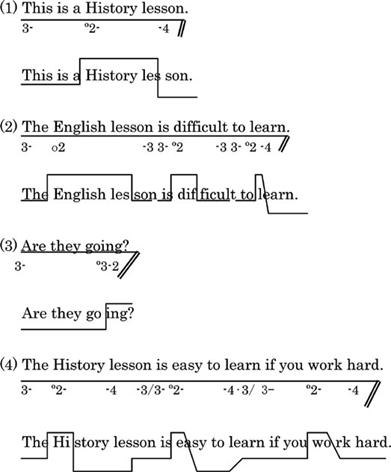

A problem that has troubled phoneticians very considerable is how to devise a practical system of recording intonation. It should ideally be easy to write, print, and read, but so far we have not arrived at an ideal method.

The following are some of the well-known methods devised by various phoneticians. They are listed approximately in a chronological order, but neither exhaustiveness nor exact arrangement is claimed.

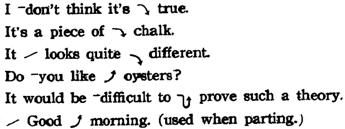

Henry Sweet17 devised

a system to indicate a rising tone ![]() , heard in questions, such as What?;

a falling

, heard in questions, such as What?;

a falling ![]() , in answers to questions such as

, in answers to questions such as ![]() No!; a falling-rising

No!; a falling-rising ![]() , as in

Take

, as in

Take![]() care!

; and a rising-falling

care!

; and a rising-falling ![]() , as

in

, as

in ![]() Oh!:

as an exclamation of sarcasm. The tone marks were put before the word

they modified; if they modified a whole sentence, they were put at the end

of it. If no tone-mark was written, a comma or a question mark implied a rising

tone, a colon or semicolon a falling tone.

Oh!:

as an exclamation of sarcasm. The tone marks were put before the word

they modified; if they modified a whole sentence, they were put at the end

of it. If no tone-mark was written, a comma or a question mark implied a rising

tone, a colon or semicolon a falling tone.

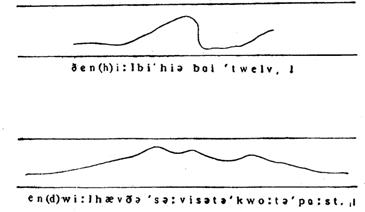

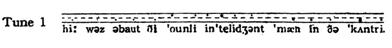

Subsequently Daniel Jones18 demonstrated by drawing speech curves on a musical staff that intonation was in almost constant movement. He obtained these curves by picking up the needle of a gramophone at various points during the playing of each syllable, and charting the pitches which he heard. Thus, the sentence, “Then he’ll be here by twelve, and we’ll have the service at a quarter past,” was recorded like this:19

H.O. Coleman, taking a hint from Jone’s curves, devised what he called numerical notaion.20 He divided the pitch variations into nine degrees, giving each syllable one or more of the figures 1 to 9. He hoped his method of notation would be found clear and sufficientlyt exact, while involving no typographical difficulties. To cite a few examples adapted from his article:

6-1 1 3 4 9 1 1 1-8

Why, you never had one before.

2 3 5 2 2 2 4-6 8-1

They answered with a prolonged “Oh”

4-2-3 3 3 4 4 5 6 1

Eight is the number she SPOKE of.

(The capitals indicate sentence stress.)

In 1922 Harold E. Palmer, in his English Intonation21 showed that the sentence could be broken into several parts of one or more syllables each, and that each part might have its own intonation contributing to the whole. These parts he called the nucleus, head, and tall of the intonation. By means of a horizontal or slanting bar for the head and about half a dozen kinds of arrows for the nucleus he managed to describe many small variations of English intonation, the marks leading themselves to facility of printing. Later,22 in 1933, the same author selected six of the most useful intonation patterns giving them somewhat fanciful terms, Cascade, Dive, Ski-jump, Wave, Snake, and Swan. Examples of his tonetic notation from his latter work are given below.

Note that in Palmer’s notation the initial

syllables or words left unmarked have a medial or a low tone, that the falling

tone indicated by ![]() or

or ![]() occurs in the syllable that follows the

mark, the remaining syllables keeping a low tone all through, and that the

modulations shown by the head-marks

occurs in the syllable that follows the

mark, the remaining syllables keeping a low tone all through, and that the

modulations shown by the head-marks ![]() and

and ![]() , and the rising arrows

, and the rising arrows ![]() and

and ![]() are distributed all over the following syllables.

are distributed all over the following syllables.

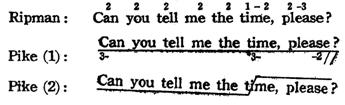

In the same year that Palmer’s English Intonation appeared, Walter Ripman published some material with intonation marks.23 These symbols were similar to H. O. Coleman’s except that they were mostly of three figures 1 to 3; very occasionally figures 4 and 5 being used. This notation of Ripman’s might well give an indication that English intonation is subject to an analysis in terms of four levels of tone. Examples from his passages analyzed are as follows:

1 2 2 1 1 3 2 1

The labour of the day is done.

1 2 3 3 3 3 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2-1

The mysterious spirit has gone to take its airy rounds.

4 4 2 3 3 3 3 3 - 1

Write me as one that loves his fellow-men.

2 5 4 5 5 4 3 2 - 1

And lo! Ben Adhem’s name led all the rest.

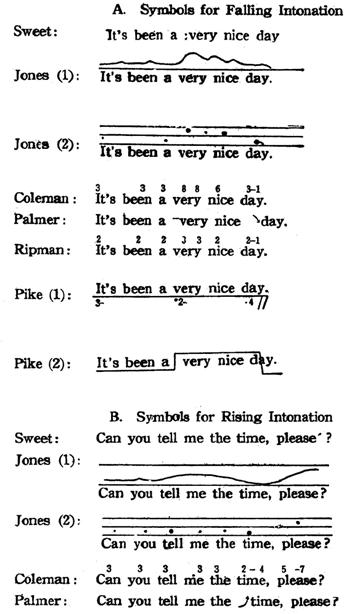

In 1926, Lilias E. Armstrong and Ida C.

Ward published an entirely different analysis which made an influential

contribution to the field.24 Their system was later adopted by

Daniel Jones, in his Outline of English

Phonetics, 3rd edition, 1933, and by Maria Schubiger,

in her Role of Intonation in Spoken

English,

Note that in this marking the bigger dots indicate that the corresponding syllables are stressed.

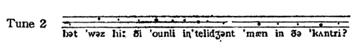

Last on our list comes that most recent and important work done in the field of American English by Kenneth L. Pike.26 He approached the problem from a phonemic point of view, so to speak, and selected a limited number of intonation types which would serve the foreign student most practically and simply. He holds that a frame of the relative pitch levels that are significant in American English consist of four steps:

No. 1 = extra high

No. 2 = high

No. 3 = medium (Basic voice level)

No. 4 = low

In natural speech there well always be fluctuations, but these fluctuations are not significant; that is, they do not matter linguistically. It is the points where the pitch levels change that are signifficant.27

Pike transcribed intonation in two ways; either by means of lines, as:

![]()

or by numerical figures, as:

![]()

The sign ![]() shows that the ‘primary contour,’ or as

Palmer and others put it, the nucleus of the intonation pattern, begins there.

The hyphen after or before a figure shows that the particular pitch is part

of an intonation contour to be complete with the following or preceding pitch

level or levels.

shows that the ‘primary contour,’ or as

Palmer and others put it, the nucleus of the intonation pattern, begins there.

The hyphen after or before a figure shows that the particular pitch is part

of an intonation contour to be complete with the following or preceding pitch

level or levels.

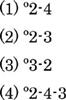

Under the pressure of teaching English as foreign language Pike selected the following four primary contours:

Each of these four contours may also appear with the precontour 3-. The following examples are given to show these selected contours.

Note: A slanting line shows that the pitch rises or falls within the syllable marked. In numerical notation a single slanting line shows the division of possible breath-groups and a double one the end of an utterance.

5.

Comparative Tables of Types of Tonetic Notation

Partly by way of summary of the preceding section and partly for purposes of comparing different types of notation given to the same kind of pitch modulations we give below in tabular form two illustrative sentences with tonetic symbols.

Note: As it is impossible to find sentences treated commonly by the individual authors mentioned above, we have marked the sentences as nearly as we could imagine the authors would have done.

6.

Comparison of So-called British and American Intonation

There are doubtless considerable differences between British and American habits of intonation. Very little has been done, however, in comparative studies of the two. Nor is it easy to compare them, because of the scantiness of literature, especially of American intonation now available.

It has been pointed out that the intonational patterns of British and American English are essentially the same.28 This means that none of the differences is ‘significant’ or important enough to change the meaning. In other words, the two habits of intonation are mutually understandable to both types of speakers.

One of the differences pointed out by many writers is that American speech normally consists of a smaller range of tonal rise and fall, particularly in regard to the higher pitches. This is obviously one of the reasons why American English sounds to our ears more monotonous than British English.

Another of the differences often pointed out is that in American speech the ‘precontour’, or the unstressed head of the phrase, is normally mid or low pitched and very seldom high pitched as is often the case with British speech. It may safely be stated that the patterns which H. E. Palmer indicated as containing a high head (‘Cascade’ and ‘Wave’) are normally replaced in American speech by those starting on a much lower-and often less stress-tone.29

For example:

British: I![]() don’t think it’s

don’t think it’s ![]() true.

true.

![]()

British:

![]() Are you

Are you ![]() there?

there?

![]()

Similarly, it seems to us that Palmer’s ‘Ski-jump’ and his ‘Snake’ pattern with a high-pitched head have no place in normal American speech. For example:

British: How

![]() strange it is!

strange it is!

![]()

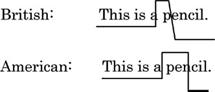

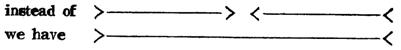

A third point of difference we may note is that in British speed changes of tone more normally proceed by glides, or continuous rise or fall, especially in the primary contour, while in American speech they more normally proceed by leaps or steps when the primary contour falls on a word of more than one syllable or a phrase.

Thus:

The above is a description

of some of the features more or less characteristic of the so-called British

and American English. Warning is however needed against hasty conclusions that

the two types of speech are clearly separated by the

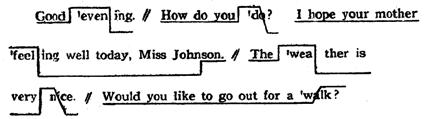

7. Specimen

Passages with Stress and Intonation Marks

A. After K. L. Pike

B. The Same Passage with Tone Marks after H. E. Palmer

(Transcribed in Phonetic Alphabet)

![]()

IV. Other Problems of Phonetic

Sequence

1.

Length of Sounds

The length of a sound, or

the length of time during which a sound is held on continuously in utterance,

usually varies according to its phonetic context. A trained ear can distinguish

many degrees of length, but for practical purposes it is sufficient to distinguish

two degrees, long and short. When it is desired to distinguish an intermediate

degree, this intermediate degree may be termed ‘half-long.’30

A. Length of English Vowels

The main facts concerning length in English sounds are given in the following rules.31

Rule 1. Those vowels called ‘long vowels’ and written in some types

of notation with the length-mark ![]() and also the ‘diphthongs’ are longer than

the other English bowels in similar phonetic context.Thus

the vowels in bead, bard, board, food,

bird, bowed are longer than the vowels in bid, bed, lad, rod, good, bud.

and also the ‘diphthongs’ are longer than

the other English bowels in similar phonetic context.Thus

the vowels in bead, bard, board, food,

bird, bowed are longer than the vowels in bid, bed, lad, rod, good, bud.

In General American the four

vowels in pit, pet, put, nut are

shorter than the rest. Other vowels, such as those in glass [![]() l

l![]() s], box [b

s], box [b![]() ks], dog [do

ks], dog [do![]() ], are generally pronounced

fairly long even if they are not followed in written symbols by the length-mark.32

], are generally pronounced

fairly long even if they are not followed in written symbols by the length-mark.32

Rule 2. All English vowels, whether long, diphthongal, or short, are shorter when followed by a voiceless consonant than when they are final or followed by a voiced consonant. Thus the vowels in seat, pierce, hit are shorter than the corresponding vowels in see or seed, pier or beard, hid.

Rule 3. All English vowels, whether long, diphthongal, or short, in strongly stressed syllables are shorter when a non-stressed syllable immediately follows in the same word. Thus the first vowel in reader is shorter than that in read, and the first vowel in running is shorter than that in run.

Rule 4. All English vowels, whether long, diphthongal, or short, are

shorter in non-stressed syllables than in strongly stressed syllables. Thus

the vowels in the unstressed syllables in although,

partake, idea until are shorter than the corresponding vowels in also, party, island, under. The so-called

‘schwa’ [![]() ], when representing an obscure vowel

as distinguished from the sound represented in some types of notation by the

symbol [

], when representing an obscure vowel

as distinguished from the sound represented in some types of notation by the

symbol [ ![]() ], is especially short and even drops

out altogether in an unstressed syllable, as in of

course [(

], is especially short and even drops

out altogether in an unstressed syllable, as in of

course [(![]() )vk

)vk![]() s or (

s or (![]() )fk

)fk![]() s], history [h

s], history [h![]() st(

st(![]() )ri]. The same vowel which occurs in a stressed syllable is

regarded as normal in the north of

)ri]. The same vowel which occurs in a stressed syllable is

regarded as normal in the north of

B. Length of English Consonants

Rule 5. Final consonants are longer when preceded by a short vowel than when preceded by a long vowel or diphthong. Thus the [n] is longer in pen than in pain or seen, and the [l] is longer in hill than in heel or hole.

Rule 6. The consonants [m], [n], [1], are longer when followed by voiced consonants than when followed by voiceless consonants. Thus the [m] in number is longer than that in jumper, the [n] in wind is longer than that in wink, and the [l] in hold is longer than that in bolt.

2. Sound-Junction

and Word-Linking

Sounds are usually affected more or less by other sounds near to them in the phonetic sequence. The chief factor in the occurrence of variant sounds in a phoneme is the nature of the adjacent sounds. This will be illustrated in the following paragraphs. Sounds are affected by their adjacent sounds whenever they occur in a continuous sequence, both within a word and in neighboring words. Sounds are also affected by their position in a word, by the degree of stress with which they are pronounced in a word, and so forth. When sounds are unstressed the tongue is more lax, and hence undergo phonetic changes.

A. Use of Incomplete Plosive consonants34

When a plosive consonant is followed by another

identical or different plosive or by [t![]() ] or [d

] or [d![]() ], the articulating organs take up their position for the second consonant

before the articulation of the first

is completed. Thus the plosion of the first

consonant is either extremely weak, or completely inaudible, or, in the junction

of two identical or similarly articulated plosives, the stop is held on from

the beginning of the first to the release of the second. To show this graphically,

], the articulating organs take up their position for the second consonant

before the articulation of the first

is completed. Thus the plosion of the first

consonant is either extremely weak, or completely inaudible, or, in the junction

of two identical or similarly articulated plosives, the stop is held on from

the beginning of the first to the release of the second. To show this graphically,

No Separation of the vocal organs takes place

between the two plosives [pp], [pb], [bp],

[tt], [td], [dt], [tt![]() ], [dd

], [dd![]() ], [dt

], [dt![]() ], [kk], [k

], [kk], [k![]() ], [

], [![]()

![]() ],

[

],

[![]() k].

k].

For example:

lamp-post

[l![]() mppoust] ([p] lengthened)

mppoust] ([p] lengthened)

went down

[w![]() nt d

nt d![]() un] (Vocal cords begin to vibrate in

the middle of the stop.)

un] (Vocal cords begin to vibrate in

the middle of the stop.)

bed-time

[b![]() dt

dt![]() im] (Vocal

cords stop vibrating in the middle of the stop.)

im] (Vocal

cords stop vibrating in the middle of the stop.)

B. Nasal and Lateral Plosion35

When a plosive consonant is immediately followed

by a nasal, as in button ![]() written

[r

written

[r![]() tn],

sudden

tn],

sudden ![]() shopman [

shopman [![]()

![]() pm

pm![]() n], oatmeal [

n], oatmeal [![]() utm

utm![]() l],

the plosive is not pronounced in the normal may. The explosion in such plosives

is produced by the air suddenly escaping through the nose, instead of the mouth. Many Japanese are apt to pronounce them in the normal

way and to insert erroneously the vowel [

l],

the plosive is not pronounced in the normal may. The explosion in such plosives

is produced by the air suddenly escaping through the nose, instead of the mouth. Many Japanese are apt to pronounce them in the normal

way and to insert erroneously the vowel [![]() ] between the plosive and the nasal.

] between the plosive and the nasal.

When [t] or [d] is immediately

followed by the lateral consonant [l], as in little [l![]() tl], middle [m

tl], middle [m![]() dl],

the plosive is not pronounced in normal way. The explosion of the plosive

is not pronounced in the normal way. The explosion of the plosive in such

groups is produced through the sides of the tongue, with the tongue-tip pressed

against the teethridge. If the plosive is pronounced normally, as is often

the case with many Japanese, the effect tends to be an erroneous insertation of the vowel [

dl],

the plosive is not pronounced in normal way. The explosion of the plosive

is not pronounced in the normal way. The explosion of the plosive in such

groups is produced through the sides of the tongue, with the tongue-tip pressed

against the teethridge. If the plosive is pronounced normally, as is often

the case with many Japanese, the effect tends to be an erroneous insertation of the vowel [![]() ].

].

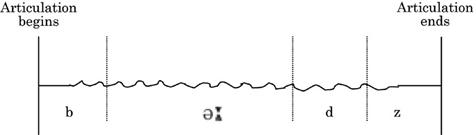

C. Partial Devoicing of Voiced Consonants

In English, most voiced consonants,

more especially the voiced plosive [b], [d], [![]() ], and voiced

fricatives [v], [z], [

], and voiced

fricatives [v], [z], [![]() ],

], ![]() , are fully voiced only when they come

between two other voiced sounds. In initial and final position they are regularly

‘devoiced’ to a greater or lesser extent. This may be shown for the word birds [b

, are fully voiced only when they come

between two other voiced sounds. In initial and final position they are regularly

‘devoiced’ to a greater or lesser extent. This may be shown for the word birds [b![]() rdz]

by a diagram, thus:36

rdz]

by a diagram, thus:36

Note: Devoiced

articulation is shown by —— in contrast with the voiced articulation

shown by ![]() .

.

Many Japanese are apt to use

fully voiced consonants where partially devoiced ones are needed, so that

in their pronunciation of a final voiced consonant a slight additional [![]() ] is hard. It may be noted in passing

that the degree of devoicing varies according to individual speakers, the

style of speaking, the phonetic context, etc. With some speakers voiced consonants,

particularly voiced fricatives, often sound as if they were voiceless.

] is hard. It may be noted in passing

that the degree of devoicing varies according to individual speakers, the

style of speaking, the phonetic context, etc. With some speakers voiced consonants,

particularly voiced fricatives, often sound as if they were voiceless.

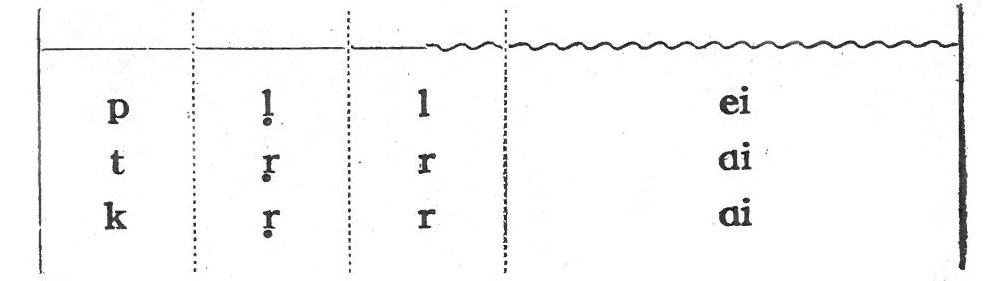

Partial devoicing of English voiced consonants takes place also in

the articulation of [l] or [r] before a strongly stressed vowel, when it is

preceded by [p], [t], or [k]. Thus play,

try, and cry might be transcribed ![]() and

and ![]() 37 respectively, apart from the length of the

consonants. In a diagram these words may be shown thus:

37 respectively, apart from the length of the

consonants. In a diagram these words may be shown thus:

D. Juxtapositional elision and Assimilation

(1) Elision is “the disappearance of a sound.”38 It is important to know in what kind of phonetic sequence a sound which exists in a word said by itself is dropped when a word is linked with another.

There are many kinds of such elisionl, which often escape the notice of foreign students of English. The degree and frequency of elision depends chiefly on the speed of speaking; the more rapid the speaking is the greater the frequency of elisions. The following are examples of juxtapsidonal elisions commonly made in ordinary (not rapid) speech:

kind man ![]() (elision of [d])

(elision of [d])

sit down ![]() (by some people; elision of [t])

(by some people; elision of [t])

take

care [t![]() ik

ik![]()

![]() ] (elision of [k])

] (elision of [k])

In deliberate speech these juxtapositional elisions are less frequently heard.

(2) Assimilation is “the process of replacing a sound by another sound under the influence of a third sound which is near to it in the word or sentence.”39 It is important to know how sounds are assimilated by their neighbors in a particular sound-sequence.

There are many types of assimilation. The most important are (1) assimilations of breathed consonants to voiced ones, and voiced consonants to breathed ones, (2) assimilations affecting the position of the organs in pronouncing consonants.

Examples of assimilation:

(1) (a) The reduced forms of is and has.

Tom is here. [t![]() m

z h

m

z h![]()

![]() .]

.]

Tom has been here. [t![]() m

z bin h

m

z bin h![]()

![]() .]

.]

Jack is here. [d![]()

![]() k

s h

k

s h![]()

![]() .]

.]

Jack has been here. [d![]()

![]() k

s bin h

k

s bin h![]()

![]() .]

.]

(b) The ending ‘-s’

(Plurals) boys [boiz], pens [penz], knives [n![]() ivz].

ivz].

books [buks], caps

[k![]() ps], hats [h

ps], hats [h![]() ts]

ts]

cf. faces [f![]() isiz], roses [r

isiz], roses [r![]() uziz],

houses

uziz],

houses ![]()

(Posessives) girl’s [![]()

![]() lz], girls’ [

lz], girls’ [![]()

![]() lz], Bob’s [bobz], Mary's [m

lz], Bob’s [bobz], Mary's [m![]()

![]() riz].

riz].

cook’s [koks], cooks’ [koks],

Jack’s [d![]()

![]() ks],

Bett’s [bets].

ks],

Bett’s [bets].

cf. horse’s ![]() , horses’

, horses’ ![]() , fox’s [f

, fox’s [f![]() ksiz],

foxes’ [f

ksiz],

foxes’ [f![]() ksiz],

Jones’s [d

ksiz],

Jones’s [d![]()

![]() unziz],

Jones’ [d

unziz],

Jones’ [d![]()

![]() unz].

unz].

Note: The ending -s of the Third Person Singular Present Verb is treated in the same way as that of the noun.

(c) The ending ‘-ed’.

showed [![]() oud], robbed [robd], begged [be

oud], robbed [robd], begged [be![]() d], looked [lukt],

dropped [dropt], missed [mist], wished [wi

d], looked [lukt],

dropped [dropt], missed [mist], wished [wi![]() t].

t].

cf. wanted [w![]() ntid], banded [b

ntid], banded [b![]() ndid].

ndid].

(d) The word ‘used’.

| Compare | The knife was used to cut it. | |

| I used to cut with a knife. | ||

(e) The word ‘have’.

I have to ask him. ![]()

I have to do it. ![]()

Note: In ‘have to’ the pronunciation [h![]() f

tu], [h

f

tu], [h![]() f

t

f

t![]() ] is common in ordinary speech in both

the

] is common in ordinary speech in both

the

(f) Miscellaneous.

| Compare | the news in the paper | |

| the newspaper41 |

||

It cost fivepence. ![]()

(2) Replacement of [s] by [![]() ], or of [z] by [

], or of [z] by [![]() ].

].

horse-shoe ![]()

this shop ![]()

Yes, she is. [j![]()

![]()

![]() i

i![]() z.]

z.]

Does she? ![]()

butcher’s shop [b![]() t

t![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() p]

p]

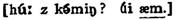

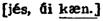

E. Some Cautions concerning Word-Linking

In English all words and syllables beginning with a vowel should in

connected speech be normally linked with the final sound of a preceding word

or syllable. This simple rule is not always observed in the pronunciation

of many Japanese, the effect of which is an insertion of a glottal stop ![]() 42 where no such

sound should occur. Thus It is on an armchair is in their pronunciation

42 where no such

sound should occur. Thus It is on an armchair is in their pronunciation

![]()

![]() whereas it should be

whereas it should be ![]() or more naturally,

or more naturally, ![]()

When

a word ending with the letter r (e)

is immediately followed by a word beginning with a vowel sound, then an

[r] sound is generally inserted in the pronunciation of Southern British.

Thus far by itself is pronounced ![]() , but when it is followed by away

the two words are linked by an [r] sound, as

, but when it is followed by away

the two words are linked by an [r] sound, as ![]()

There are, however, special circumstances in

which a final r(e) is not pronounced

in the linking. The principal cases are (1) when the vowel in question is

preceded by [r], for example, the Emperor

of Japan ![]() nearer and nearer [n

nearer and nearer [n![]()

![]() r

r![]()

![]() nd n

nd n![]()

![]() r

r![]() ]; (2) when a pause is possible

between the two words (even if no pause is actually made), for example, he

shut the door and went away

]; (2) when a pause is possible

between the two words (even if no pause is actually made), for example, he

shut the door and went away ![]()

It is to be noted, however, that in Southern British the insertion of a linking r is not essential, there being many people who do not insert it where others do.43 In General American no linking r as such is necessary, as all final r’s in the spelling are sounded.

3.

Relation between Rhythm and Sentence-Stress

There is noticed a strong tendency towards rhythmic regularity of strong stressed in connected English speech. This gives rise to the following important variations in the normal stressing of words and syllables.

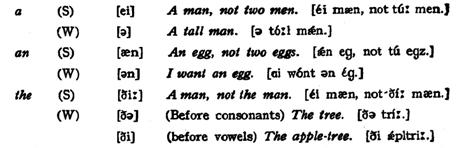

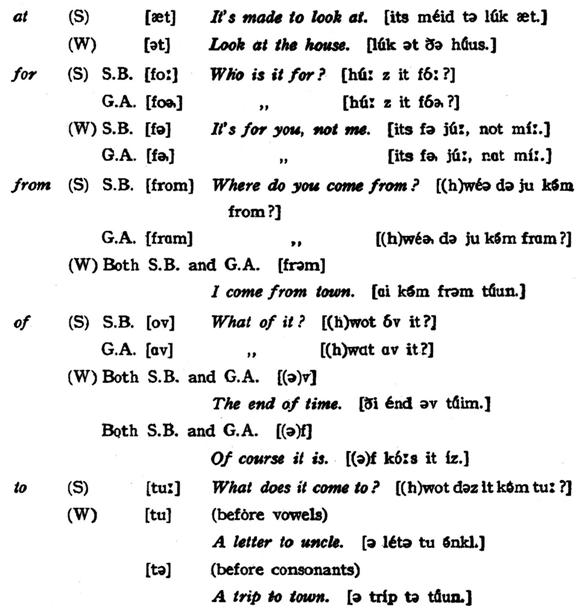

(1) “Double-stressed” words,